Organizational excellence is about people performing better together—and herein lies the far-reaching role of leadership.

The people side of business, government, politics, international affairs and so forth, is the gist of the confluence of all these fields.

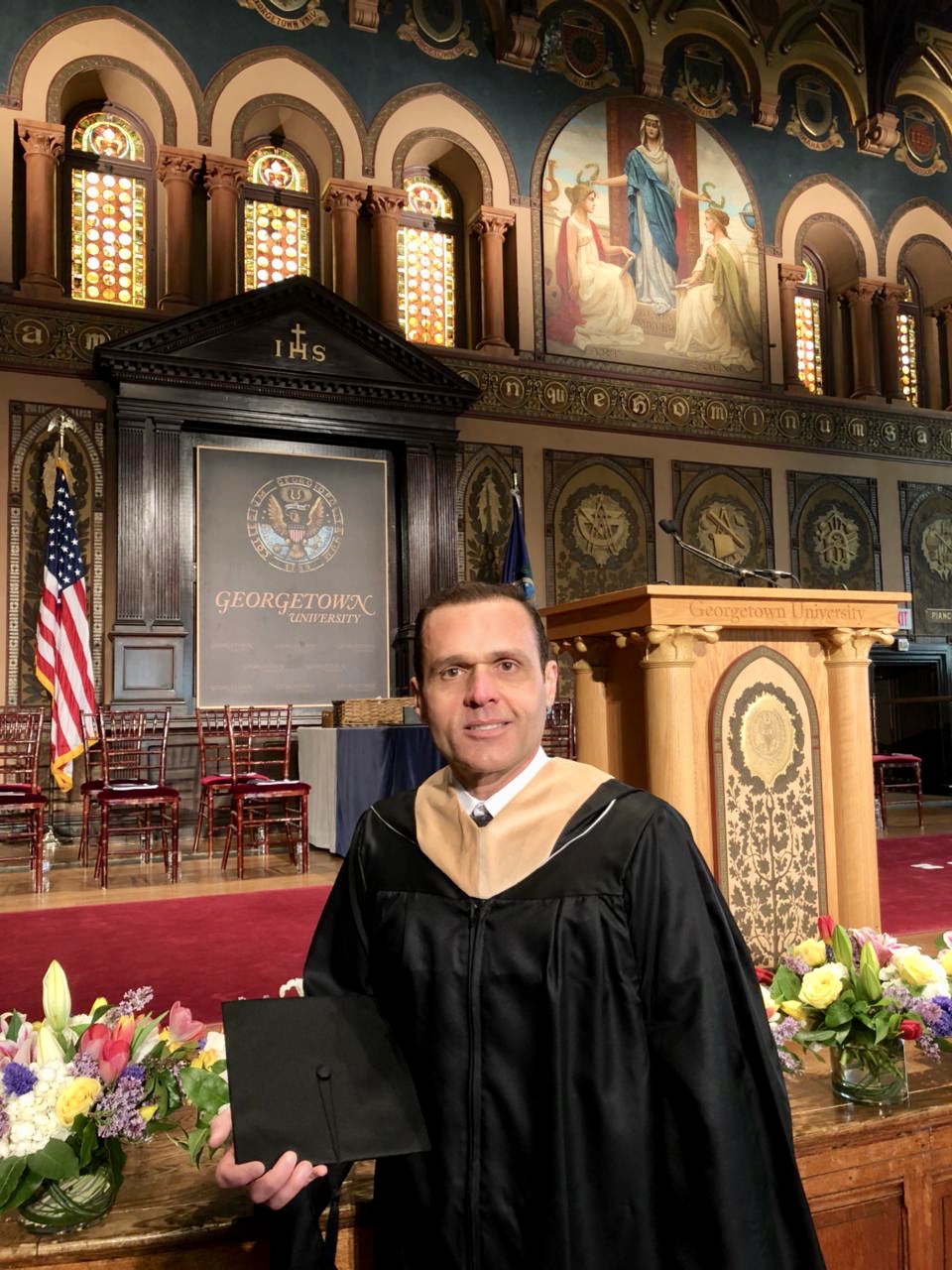

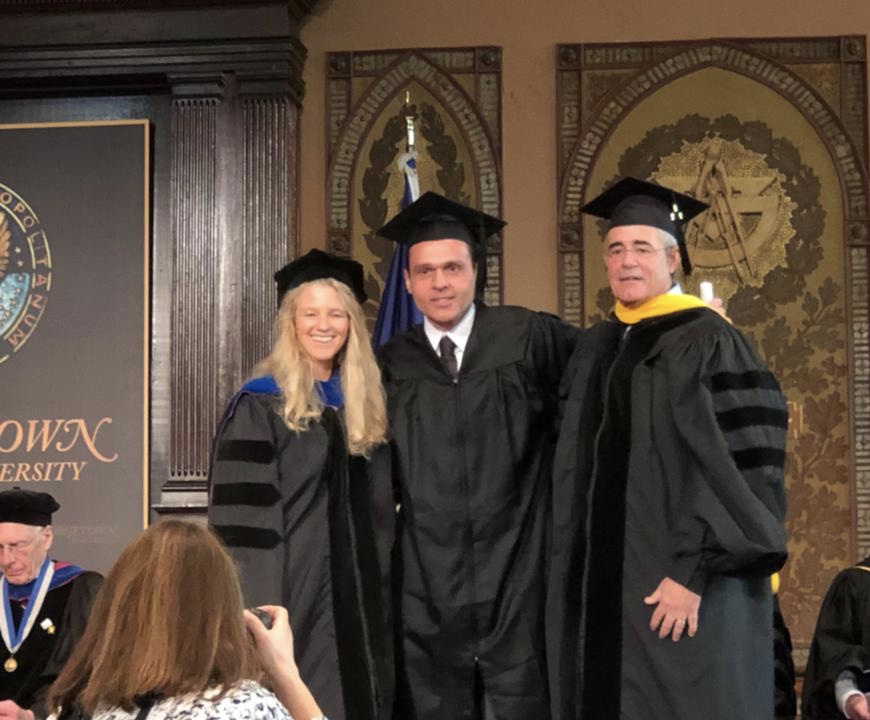

Precisely from this intersection, I studied both the art and the science of leadership, as well as pondered on the body of knowledge—all at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business, in Washington, D.C.

Thereby, my Capstone Project was “An Analysis of the Role of Followership in Influencing Leadership: How Followers Can Foster a New Generation of Principled and Transformational Leaders.”

Mirroring the goal of my book “It Was About Hope,” again I share facts and insights that may be examined, and may then spawn new thoughts, new theories, and new conclusions.

Such a ripple-effect would be gratifying, mainly, because I honor a vital element: We are all entitled to respectfully and openly make our own critiques; likewise, to freely make our own assessments and determinations.

Seeing all that, I decided to make my Master’s Paper available bellow today—the day I graduated from GU.

To sum it all up, this study is a work in progress, which is dedicated to both whoever is willing to share his/her wisdom to perfect it, and to whomsoever may find it valuable in any measure: If you fall into either category, this study is dedicated to you!

***

Excelência organizacional se traduz por pessoas que juntas realizam mais e melhor—e aqui reside o fundamental papel da liderança.

O lado “pessoas” dos negócios, governo, política, assuntos internacionais e etc, é o coração da interseção de todos esses campos.

Precisamente desta confluência, eu estudei tanto a arte quanto a ciência da liderança, examinando o conjunto do conhecimento firmado—tudo na McDonough School of Business da Georgetown University, em Washington, D.C.

Nesse contexto, a minha Tese de Mestrado foi “Uma Análise do Papel dos Seguidores ao Influenciar os Líderes: Como os Seguidores Podem Promover uma Nova Geração de Líderes de Princípios e Transformacionais”.

Semelhante ao objetivo do meu livro “It Was About Hope”, novamente compartilho fatos e reflexões que podem vir a ser examinados, e assim gerar novos pensamentos, novas teorias e novas conclusões.

Tal efeito aperfeiçoador das minhas observações seria demais gratificante, principalmente, porque eu honro um valor fundante: todos nós temos o direito inalienável de, respeitosa e abertamente, produzir nossas críticas; do mesmo modo, livremente fazer nossas avaliações e tomar nossas decisões.

Considerando tudo isso, decidi hoje disponibilizar abaixo o texto da minha Tese—dia da minha graduação na Georgetown.

Resumindo tudo, este estudo é um trabalho em progresso, o qual é dedicado a quem quer que esteja disposto a compartilhar sua sabedoria para aperfeiçoá-lo, bem como a quem quer que o considere útil em alguma medida: se você se enquadra em alguma dessas categorias, este estudo é dedicado a você!

*************************************************************************************************************************************

An Analysis of the Role of Followership in Influencing Leadership:

How Followers Can Foster a New Generation of Principled and

Transformational Leaders in the U.S. and worldwide

Master’s Paper

Presented by Eduardo Diogo

April, 2018

Executive Master’s in Leadership Degree

McDonough School of Business

Georgetown University

Washington, D.C.

Faculty Mentor: Professor Matthew A. Cronin

Faculty Reader: Professor Laura Morgan Roberts

Contents

Abstract 2

Introduction 3

Method 11

Definition of Problems. Followership: Description and Types. Examples of Follower-Leader Interplay. 13

Definition of Problems 13

Followership: Description and Types. Examples of Follower-Leader Interplay. 15

Origin of the Problems 21

The Aspirational Qualities of Followers 23

Solution, Recommendations, and Conclusion 29

References 37

Abstract

This Master’s Paper examines the understudied role of followership in the selection and development of principled and transformational leaders. The prime reference for this study was the 2016 presidential election in the U.S. The study also outlines the attributes of a Regenerative Leader, and considers whom might represent an accurate example of this type of leadership in our present-day world. Regarding followership, this research aims to (a) define it, (b) subdivide it into two overall groups, and (c) delve into the aspirational qualities of followers. This examination also makes a claim on the origin of the three main problems that affect leadership-followership, and the descriptions of those problems consider both the “internal ecosystem” (the one that lies within us) and the “external ecosystem” (the factors that influence us from outside). The exploration of the latter is divided into two parts, investigating both the world in general, and the United States in specific. In this respect, this Paper presents recommendations that aspire to accommodate Democratic voters, Republican voters, Third Party voters, and Independent voters. Ultimately, the notion of a universal “wake-up call” is embedded in the observations printed here, which assert the imperative necessity of developing a superior followership and leadership—in every corner of the world.

Introduction

With this Capstone Paper, I intend to suggest new approaches and insights for perfecting both the follower-leader relationship—and American Democracy more broadly. Thus, it is essential to establish an accurate starting point, so therefore this Paper will begin with the firm premise that followers do hold sway over leaders.

As the title suggests, the topic of this Master’s Paper is “The Role of Followership in Influencing Leadership,” and its research question is “How Can Followers Foster a New Generation of Principled and Transformational Leaders?”

The key distinction here is in the choice to place “followers” ahead of “leaders.” In other words, this study acknowledges not only that followers hold sway over leaders, but also that followers, in fact, take precedence over leaders. It seems unlikely that anyone would dispute that, by definition, any follower-leader relationship, or leader-follower relationship, is at the very least a two-way exchange.

This concept is supported by Paul and Blanchard in “Situational Leadership Theory” (1985). In a situational leadership context, argument preponderates over authority, so therefore guidance is provided per expertise, not per power per se. Centuries before Christ, Aristotle himself already stated that “he who cannot be a good follower cannot be a good leader.” In others words, leaders and followers are involved in a permanent, ongoing process of exchange; and for a successful leader-led interaction to occur, both an adaptive leadership style and the existence of a mature followership are required.

Therefore, considering leaders as the locomotives that supply motivational power to this system, I argue the following: good leaders understand that one of the most important tasks of any government, any party, and any institution or organization (related to the present subject matter) is to foster a new generation of principled and transformational leaders; however, only great leaders fully understand the task of fostering a new generation of astute and transformational followers.

Evidence suggests that neither of these two modalities can be said to dominate the current global arena. For instance, the 2016 presidential election revealed how detrimental is not promoting fresh leaders, and the former President Barack Obama was a sort of incarnation of this reality. After almost eight years in office, President Obama had fostered zero new leaders not only for his party, but also for his country.

In the Democratic Party, the two main names that disputed the nomination were Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders (who is, in fact, an Independent politician), and they were respectively 69 and 75 years old (this was the picture as of November 8, 2016—Election Day). Regarding Obama’s administration, it mirrored his own party. Reporting the age of the occupants of four top positions close to President Obama, this was the image as of the same date: Vice President: 74-year-old Joe Biden; Secretary of State: 73-year-old John Kerry; Minority Leader in the Senate: 77-year-old Harry Reid; and Minority Leader in the House: 76-year-old Nancy Pelosi.

The inexistence of fresh leaders leads to the inexistence of fresh followers, so therefore the symptoms of premature aging prevail. This vicious cycle could be identified in Obama’s era. During his presidency, the Democratic Party reduced significantly: “U.S. Senate seats: 9 losses— the Democrats fell from 55 to 46; U.S House seats: 62 losses—the Democrats fell from 256 seats to 194; Governorships: 12 losses—the Democrats fell from 28 to 16; State Legislative seats: 958 losses” (Diogo, 2017, p. 696). Specifically with regard to the U.S. Congress, when Barack Obama ran for President in 2008, the Democratic Party had a majority both in the U.S. House and in the U.S. Senate, and both were lost during his Presidency—to be precise, when President Obama left office the Democrats had the smallest congressional minority since 1929.

Sadly, the United States is a representation of the overall myopia of many of the world’s current leaders. Regardless of whether those leaders are playing their leadership development strategies by ear, or intentionally doing a poor job on this front; it is undeniable not only that the failure to cultivate strong leadership is our primary problem, but also that those modern leaders are the main responsible for this current trajectory worldwide.

Consequently, it is becoming increasingly difficult to identify our new Joans of Arc, Mother Teresas, Mahatma Gandhis, and Nelson Mandelas. I include them as models of what I consider to be Regenerative Leaders. These can be summarized as inspiring, altruistic figures, whose unflinching beliefs have played a decisive role in engraving their names on the history of mankind, due both to the feats they accomplished during their lives, and to the exemplary moral legacy that they left to shape future generations.

Putting it differently, Regenerative Leaders deliver a leadership style that transcends the well-known four I’s of “Transformational Leadership” (Bass, 1985). Thus, using this existing concept as a foundation to generate our new conception, I will outline here the 11 attributes that define Regenerative Leaders:

- They embrace the Infinite Improvement—what could even be considered as a “fifth I,” if you will. Regenerative Leaders know the tiny little fraction they do, and are aware of the myriad of issues that they do not know. Thus, they are humble enough to study what is unknown to them so that they may assuage their lack of knowledge in the topics at hand. They understand that the adoption of the never-ending process of unlearning and relearning is both rejuvenating and indispensable. Given that one may see similarity between the “Infinite Improvement” and the “Intellectual Stimulation” (of the “Transformational Leadership” theory), it is opportune now to make a clear distinction between them: in the former idea leaders challenge themselves to excel; in the latter idea leaders challenge followers to excel—they are complementary to each other indeed.

- They have lack of attachment to power itself. To better explain this virtue, I will point out a feature of my mother language. In Portuguese, the verb “to be” is represented by two distinct verbs, so that while one expresses a temporary circumstance (“estar,” e.g., I am President of the U.S.), the other reflects a permanent condition (“ser,” e.g., I am Donald Trump). Regenerative Leaders have lack of attachment to power itself first and foremost because they fully comprehend this distinction, and also because they know both that power is ephemeral, and that serving in a public office is not about themselves personally—but about the collectivity.

- They give credit where credit is due—again, they are able to do this because they understand that the journey is not about them, but it is a collective endeavor. As a result, they not only appreciate peer networking, but are also unashamed of emulating someone else’s good practices. This whole notion also helps them to seize the power of long-term thinking, rejecting decision-making based exclusively upon what is good for the length of their own tenure in office.

- They know that there are no one-size-fits-all leaders. They are essentially baton holders who are willing to pass their authority to others depending on the inclinations of their followers and the subject at hand—they create leadership opportunities for everyone. This topic is a reinforcement of the “Situational Leadership” idea.

- They speak not only to the hearts of their constituents, but to the hearts of the entire population, and are heard by all. They manage to be heard by all because they indiscriminately protect, learn, teach, encourage, and love. I emphasize “love” as a characteristic of someone who does not judge the deeds of others—a detrimental pattern which has unfortunately become common in our contemporary society.

- They act based on the truth and not on fleeting convenience. They do not sugar coat reality and do not tell white lies—to themselves nor to others. They seek out the unvarnished truth for themselves and communicate it to the collective with compassion.

- They define their non-negotiables with precision, and while they are unflinching about them, they are flexible in accommodating everything else. With this mandate in place, they leave their marks on history due to their ability to pull off strategic plans that are beneficial to the many (not only the few), and due to their exemplary moral legacy, which helps to shape current and future generations.

- They cherish followers who opt to walk a nonconforming path. Regenerative Leaders are convinced not only that this path entails far more collective benefits than the obedient one, but also that it requires inter-independence. When inter-independence takes place, relationships are based on both mutual independence and reciprocity, rather than being based on mutual dependence and necessity. Inter-independent leaders and followers cooperate with one another not because they need to, nor because they are obligated to, but because they freely choose to. As a result, inter-independence is a sort of yes-man repellent—a poisonous species of follower treasured by mediocre leaders. The crux of the matter is: if one cannot say “no,” one’s “yes” is meaningless. Hence, Regenerative Leaders accept that interdependence (mutual reliance) between followers and leaders should become inter-independence (mutual self-reliance).

- They fully advocate that instead of sameness, pluralism is in fact the guarantor of complementarity, which is an indispensable factor in extraordinary outcomes. While similarity can be acknowledged to have its perks, Regenerative Leaders argue that these advantages are in fact greater when they are wisely seasoned with deviance. Otherwise, essential features, like innovation, are unlikely to emerge from such leader-led interactions.

- They uphold two fundamental principles, one informal and one legal, which are: the ability to put themselves in other people’s shoes, which is a prerequisite to building rapport, and the rule of law, which is a prerequisite to protecting the social fabric. These notions are essential to comprehend that despite our contemporary tendency toward belligerence, every human being is in the same business: happiness.

- They diligently work to foster a new generation of principled and life-changing leaders, as well as a new generation of astute and life-changing followers. They know that the condition of leadership depends upon the condition of followership; in other words, followers are as good as the quality of leaders they choose to represent them—so therefore both must be superlative to spawn both superb outcomes, and a virtuous cycle.

Seeing those 11 characteristics of Regenerative Leaders, it is not difficult to perceive the modern context faced with a scarcity of such leadership. Notwithstanding, there is at least one global leader who falls into this category: Jorge Mario Bergoglio, or Pope Francis. The 266th and current Pope of the Catholic Church is much more than a religious leader, and the U.S. is a living proof of the far-reaching leadership delivered by Pope Francis.

As per the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study (2014), 31.7% of American adults say they were raised Catholic, while 41% among these no longer identify themselves that way. In addition, the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), shows that as a proportion of all births in the U.S., Catholic baptisms have decreased from 35% in 1965 to 18% in 2014. Despite these numbers, in his five-day inaugural appearance in the U.S., in September 2015, His Holiness captivated American minds and hearts. The Pontiff—also the Head of State of the Vatican—became the first ever person in such a position to address the U.S. Congress, and on this occasion, as in all others, the multifaceted leader shone.

This perception can be demonstrated, for instance, by the presence of millions and millions of Americans in the streets to salute the Pope. In addition, a CNN/ORC poll found (also in September 2015) that 63% of Americans viewed Pope Francis favorably, and 76% assessed his positions on issues as “about right.”

Wisely, the humble and visionary Holy Father has been steadily overhauling the millenarian Catholic Church for a new millennium. This is an enormous challenge, which is not only necessary, but also specifically requires Regenerative Leadership to achieve.

Given that this Master’s Paper primarily intends to address the imbalance inherent in the understudied role of followership in the selection and development of principled and transformational leaders, one might allege that I have put too much emphasis on the concept of Regenerative Leaders. However, the fact of the matter is that we are in great need of these Regenerative Leaders to help us in promoting a new generation of followers.

Considering that, I reiterate that Regenerative Leaders “know that the condition of leadership depends upon the condition of followership… so therefore both must be superlative to spawn superb outcomes.” To finalize this section, I make a clear statement of the claim I intend to prove, and of the universal recommendation I intend to offer: it is critical for us all that followers be mindful of their role in carving their own path and the path of their nations—working side by side with the current leaders.

Method

This Master’s Paper is a Case Study that has scrupulously attempted to identify the real issues at play in the questions examined.

Given that a “case study is not a methodological choice but a choice of what is to be studied” (Stake, 2005, p. 443), one might contest the affirmation present in the former paragraph. Nonetheless, in fact case studies can not only be defined as a qualitative research method, but are also extremely attractive because they allow investigators to “retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events” (Klenke, 2008, p. 59). Surely, this present project aims to “retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of [the] real-life event” observed here, that is, the 2016 presidential election in the U.S.

I chose the 2016 presidential election in the U.S. as a primary source to complete this work, because it exposed the dynamics of the leader-follower interplay—what is the core of this examination. Additionally, because such exposition occurred wide spread, given that that election was the most recent political race somewhat observed by the entire world.

While engaged in this evidence-based research, I have:

- Described: recorded what occurred in the interactions observed.

- Interpreted: revealed and analyzed the nuances that stood out.

- Evaluated: determined what could be learned.

- Suggested: developed new solutions and recommendations.

To conclude this segment, it is worth noting that I have compiled a systematic review of the pertinent literature. The data and information used in this Capstone Paper were compiled from numerous studies, and were also of great importance in reaching the conclusions detailed here.

Definition of Problems. Followership:Description and Types.

Examples of Follower-Leader Interplay.

Definition of Problems

In the Introduction, this Paper identified problem number one (“the failure to cultivate strong leadership”). Now, this section will pinpoint problem number two (which directly affects both leaders and followers): we have become incapable of hearing each other, and of being heard by one another. As a result, consciously or unconsciously, most of us tend to see as enemies anyone who has political views slightly different than our own.

On top of that, as we take for granted the fast-paced events of our contemporary society—in which, for example, opinions are summarized in 140 characters and people prioritize online chats over in-person conversations—we are also relinquishing a foundational right that we are endowed with, which is the ability to think calmly, to ponder deeply, and to examine and appreciate matters before we externalize our perceptions, ideas, and decisions. This is problem number three (which also directly affects both leaders and followers).

By contrast, as the snapshot above suggests, pace has overtaken over direction, and anxiety has overtaken serenity. The resulting behavior leads to empty thoughts, based on vague first impressions. In addition, these inconsistent opinions may go viral in seconds via our contemporary social media environment. Hence, the impetus to show off, combined with an accelerating trend in which unfortunate judgements are over-shared, have been counterproductive and detrimental to our harmonious coexistence.

To be precise, this combination has impaired our ability to put ourselves in other people’s shoes (which would allow us to empathetically listen to one another), and has generated division, hate, and senseless rivalry. Whether we like it or not, this is part of the history of our present time. Consequently, our social fabric is torn—and the U.S. provides an accurate representation of this widespread situation (and just for the record, my Motherland, Brazil, is not an exception to this pattern).

Followership: Description and Types. Examples of Follower-Leader Interplay.

The scenario described above represents a disturbing interplay preponderantly among followers, which is exacerbated by the sectarian behavior of their leaders. In fact, those are sort of pseudo-leaders, essentially because they consider only the places they belong to, and fail to see the people as a whole—the antidote for that is prescribed in the feature number five of the 11-attribute definition of Regenerative Leaders.

Seeing that, the primary reference of this research, the 2016 presidential election in the U.S., provides accurate examples from both sides of the aisle—one which led to a defeat and another which led to a victory.

Addressing the failed argument first, the Democratic standard bearer, Hillary Clinton, was the candidate who defined everyone who did not support her during the Primaries as a “Bucket of Losers.” Clinton further defined everyone who did not support her during the General Election as a “Basket of Deplorables”—including part of this group as “irredeemable” and “not America.” Regardless of how this behavior is characterized, or what her intention may have been, it remains indisputable is that it did not strengthen her candidacy—to say the least.

Regarding the more successful approach, it was implemented by the Republican nominee Donald Trump. I will refer to this as a 100% of 100% strategy. As the election neared its homestretch in October, Trump carried out his ultimate endgame: he managed to energize his constituents to such a tremendous degree that it resulted in an exceptionally high turnout. As a consequence, this turnout represented the perfect maximization of his base (“100% of 100%”), sufficient to carry him to a win in the election.

Neither Clinton’s nor Trump’s approaches were inherently inclusive; rather they were the opposite. Differently than Pope Francis, neither Clinton nor Trump were capable to “speak not only to the hearts of their constituents, but to the hearts of the entire population, and to be heard by all.” Regardless, Clinton failed and Trump succeeded. In brief, while Trump’s strategy was focused on both downplaying his adversaries and firing up his own constituents, Clinton’s statements used her adversary’s constituency as a vessel for criticism to his own opponent—a naive mistake.

Regarding the Republican high turnout that was sufficient to carry Trump to a win in the election, it was even more successful because the Democratic leadership did not succeed in ensuring their own high turnout. Examining the last affirmation in greater detail, the Democrats have a clear way of carrying out their communications with Americans, which can be segmented into at least three subsections: demographic, geographic, and thematic.

During the 2016 race, then-President Barack Obama had a clear mission: to fire up all Democratic sympathizers—mainly African Americans—in order to secure a high turnout. Obama failed. Leading up to this result, the followers’ inaction led Obama to try opposite approaches—from a disproportionately surly manner to a humbly seductive one. These approaches are reviewed below.

On September 17, 2016, President Obama addressed the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, and, yelling at the crowd, he stated: “My name may not be on the ballot, but our progress is on the ballot… [And] I will consider it a personal insult, an insult to my legacy, if this community lets down its guard and fails to activate itself in this election.”

On October 5, 2016—three days before Election Day—a sit-down interview with President Obama was aired (HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher). On that occasion, Obama voiced the following soft-spoken appeal: “Anybody sitting on the sidelines right now, or deciding to engage in a protest vote; that’s a vote for Trump. And that would be badly damaging for this country, and would be damaging for the world. So, no complacency this time. Get out there!”

Followers reacted to this “remote orientation” with passivity—they did choose to “sit on the sidelines,” and this behavior was a pivotal factor in the Democrats’ ultimate loss. This Master’s Paper understands that there were two principal determinants that led to this apathy: Obama’s megaphone had lost part of its power; and the disposition of Americans toward Hillary Clinton was reluctant.

About the former, it was the result of a circumstance perfectly summarized by the former President Bill Clinton. On March 7, 2016, while campaigning for his wife in Raleigh (NC), he affirmed: “Millions and millions and millions and millions of people look at that pretty picture of America he [President Barack Obama] painted, and they cannot find themselves in it to save their lives. That explains everything… People are upset, frankly, they’re anxiety-ridden, they’re disoriented, because they don’t see themselves in that picture.”

Regarding the disposition of Americans toward Hillary Clinton, it was clearly portrayed in a New York Times article from April 23, 2016—written by the op-ed columnist Nicholas Kristof. Its title was “Is Hillary Clinton Dishonest?” and Mr. Kristof wrote: “When Gallup asks Americans to say the first word that comes to mind when they hear “Hillary Clinton,” the most common response can be summed up as ‘dishonest/liar/don’t trust her/poor character.’ Another common category is ‘criminal/crooked/thief/belongs in jail.’”

With those nuances consigned, it is now opportune to clarify that a regularly accepted scholarly definition of followership does not seem to have emerged yet. For that reason, for the purposes of this study I will define followership as a set of inactions or actions practiced by someone, either currently or in the future, who is, consciously or unconsciously, directed or affected by someone else. In this context, this Master’s Paper examines a set of inactions or actions practiced by someone who, in the overwhelming majority of the cases, has not even met the leader in person—as in the previous examples.

Hence, it is now the time to note that followership, as defined in this project, can be fairly represented as falling into these two distinct overall groups:

- Followership from face-to-face interaction

- Followership from remote orientation (I already mentioned this term previously)

The former has been well covered by previous research, and I consider Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX Theory) to be a fundamental element of this review.

Although this Paper will not address followership from face-to-face interaction, it is relevant to state that there is merit in the LMX’s three-phase relationship built between leaders and followers, which are: “stranger,” “acquaintance,” and “mature partnership.” However, even though it is important to recognize the presence of two pivotal nouns in the appreciation of “mature partnership” (confidentiality and loyalty), this very study also considers that the description of “mature partnership” overlooks an indispensable concept: that of inter-independence (which was already detailed in feature number eight of the 11-attribute definition of Regenerative Leaders). Inter-independence in fact is necessary in both types of followership (from face-to-face interaction and from remote orientation).

At this moment, it is important to analyze another development from the 2016 presidential election in the U.S., in order to better comprehend the role of followership in influencing leadership—through the lens of “followership from remote orientation” (the type of followership that is the focus of this work).

On April 7, 2016, former President Bill Clinton was taken by surprise at a rally in Philadelphia, where Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters started to shout: “Black youth are not super predators.” The hecklers also held a sign proclaiming, “Hillary is a murderer.”

The former POTUS could not follow the planned course of the event; thus, he sparred with the dissidents: “I love protesters… Here’s the thing. I like protesters, but the ones that won’t let you answer are afraid of the truth. That’s a simple rule… You are defending the people who killed the lives you say matter… I don’t know how you characterize the gang leaders who got 13-year-old kids hopped up on crack and sent them out onto the street to murder other African-American children. Maybe you thought they were good citizens. She [Hillary Clinton] didn’t. She didn’t.”

The controversy stems from the “1994 Crime Bill” signed by President Clinton, and Hillary Clinton’s own statement from 1996: “They are often the kinds of kids that are called ‘super predators’… No conscience, no empathy, we can talk about why they ended up that way, but first we have to bring them to heel.”

The above is only a quick recap of the issue; the focus of this argument is on the turnaround which followed Bill Clinton’s 2016 remarks. The day after the incident, the former President backpedaled, affirming: “I never thought I should drown anybody else out. And I confess, maybe it’s just a sign of old age, but it bothers me now when that happens. So, I did something yesterday in Philadelphia. I almost want to apologize for it.”

Afraid to suffer electoral damage, a former POTUS did not hesitate to forsake his convictions. This is troubling behavior: the idea of being silent about one’s beliefs, simply because they might be unpopular. This example is evidence of followers directing leaders—whom, in this case, I would define as cornered politicians. Ultimately, Bill Clinton opted to comply with the informal Democratic rule, which proclaims: “thou shalt not contradict Black Lives Matter protesters.”

As the above example shows, whether their impact is positive or negative, followers’ actions and inactions—conscious or unconscious—are decisive enough to have a tremendous impact on their leaders’ demeanor. In fact, they can have a tremendous impact even on their leaders’ lives.

Origin of the Problems

To state it straightforwardly, the origin of the three problems outlined in this Paper can be found within us.

Elaborating on problems two and three—which are the two that affect followership directly—they often appear in the form of an extreme and irrational polarization. However, I would argue that the inward, invisible polarization is even greater than the obvious outward polarization. That is, not only our conscious, but also our unconscious biases and beliefs play critical roles in directing us toward a “my way or the highway” mindset.

We can easily identify “others” acting in this dysfunctional way—but not ourselves. This misperception aggravates the situation. This occurs because, as we come to believe that polarization has taken over political parties and the mass electorate, we tend to adopt drastic policy predilections, and to verbalize harsher remarks (Ahler, 2014). This vicious cycle is explained by the study on “Pluralistic Ignorance,” which indicates that our erroneous convictions regarding others’ viewpoints may influence our own behavior (Prentice & Miller, 1996).

This pattern might begin to explain the way that Hillary Clinton acted during two distinct moments of the 2016 campaign, first at the beginning of February, and then in the beginning of November, one week before Election Day. These two illustrative incidents are examined below.

In February, Clinton decided not only to continue playing the woman card, but also to take this strategy to another level. She invited former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to introduce her at an event, so that Mrs. Albright could deliver the opening remark: “And just remember, there is a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other!”

In November (nine months later), Clinton decided to embrace a strategy which I will refer to as the Colossal-Suicidal Dose. Besides the personal jabs against Trump, she also suggested that an eventual Trump win would generate imminent civil and nuclear wars. She stated: “He [Trump] has a dark and divisive vision for America that could tear our country apart… Abraham Lincoln understood a house divided against itself cannot stand… And we fought a civil war…. Imagine him [Trump] in the Oval Office facing a real crisis. Imagine him plunging us into a war because somebody got under his very thin skin… When the President gives the order, that’s it… There’s no veto for Congress, no veto by the Joint Chiefs. The officers in the silos have no choice but to fire. And that can take as little as four minutes.”

One might argue that Clinton’s primary focus at that time was on containing Donald Trump’s momentum and on ensuring a high turnout among Democrats. Although I see merit in this argument, I consider the dose or intensity of this approach to have been irrational. And herein lies the problem with a remedy that, rather than healing the patient, ultimately kills them. The brutal approach outlined above backfired—Democratic sympathizers simply decided to disengage.

The Aspirational Qualities of Followers

To accurately address both its topic (“An Analysis of the Role of Followership in Influencing Leadership”) and its research question (“How Can Followers Foster a New Generation of Principled and Transformational Leaders?”), this Master’s Paper dedicates its first part to the former, and the second part to the latter.

Thus, as an opening to this section, I take a clear position on answering the research question: followers must encourage their current leaders to enjoy the benefits of retirement—that is, they must substitute one leader for another.

To get there we must seize the power of long-term thinking; acknowledge that our enjoyment of our comfort zone precludes the possibility of our being substantially better off in the future; and reject one of the least efficient habits: “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”—the pattern used by Albert Einstein to describe insanity.

Admittedly, putting reason first, sometimes at expense of genuine emotion, is not an easy task. After all, as the “Tale of Behavior Change” (Haidt, 2015) explains via analogy, while our rational system is represented by “the rider,” our emotional system can be depicted as “the elephant.” Namely, since “the elephant” is much stronger than “the rider,” it will often determine the path.

I note the factors above because I would argue that any change in the external ecosystem (society) must begin in the internal ecosystem (individual). Putting it differently, bettering humanity begins with bettering ourselves individually—it commences in our inner sanctum, precisely where I have already suggested we can trace the origin of the problems discussed.

In this context of change, three attributes are essential in both internal and external environments: attitude (which provides the strength to start); motivation (which provides the persistence to continue); and ability (which provides the capacity and the expertise to accomplish).

Regarding the detrimental “enjoyment of our comfort zone” noticed above, the model proposed in “Change Model: Unfreeze, Change, Refreeze” (Lewin, 1940) is a touchstone that still holds true—and it might be useful to be underlined. “Lewin’s Change Model” uses the metaphor of a big cube of ice that must be converted into a cone of ice. This process would have three steps: (1) the ice needs to be melted to make it susceptible to change; (2) the iced water can be molded into the desired configuration; and (3) the new configuration can be solidified. Once this process is concluded, the results of the change should be observed for a proper period of time, then another round of “Unfreeze, Change, Refreeze” should be applied. As a matter of fact, this is the beauty of that process of “Infinite Improvement,” both organizational and personal.

Nonetheless, for such change to be enacted, it requires proactive behavior to explain, first, why change must take effect. As Yalom (1995) affirmed: “Motivation for change must be generated before change can occur. One must be helped to re-examine many cherished assumptions about oneself and one’s relations to others.” (p. 489) This is precisely the unfreezing stage (where the entire process begins), which is critical to successfully break the inertia deep-rooted in the “enjoyment of our comfort zone.”

That said, it is time to recollect the premise I established in the Introduction (“followers do hold sway over leaders”)—that is valid worldwide, at least in respect to Democracies. Thus, we need to produce followers who have the attitude, motivation and ability to seize this advantage. We must empower our youth far beyond what the long-established approach of the present educational system has attempted—for example, with psychological strength.

We must find a way to teach key strengths, such as self-reliance, resourcefulness, introspection, eagerness, fellowship, resilience and awareness. This is a vital pre-requisite to undertaking the direction I recommended when answering our research question, and affirming that “followers must encourage their current leaders to enjoy the benefits of retirement.” In other words, this process of continual replacement must be done with wisdom, critical thinking, and rational behavior. And those seven key strengths or attributes listed above will help us to get there.

Although I am not as extreme as Galileo Galilei, who proclaimed that “we cannot teach people anything; we can only help them discover it within themselves,” I do recognize that some skills cannot be taught, they can in fact only be learned. That said, I believe that it is our generational obligation to embrace long-term thinking as a cornerstone. It is not difficult to acknowledge that we can do better, and that we must do more than what we have been doing. It is certainly possible, and as Albert Einstein proclaimed: “Once we accept our limits, we go beyond them.”

Therefore, by accepting our limits and remaining grounded in reality, we have a chance to instill a sense of urgency, a sense of purpose, a sense of community, and a sense of the future. These four goals can be considered a sort of “Goald” Pot—where “Goald” combines both “goal” and “gold.”

In this context, while I see merit in the assertion that “leaders serve as role models and champions” (Sherman & Freas, 2004), I would also argue that role modeling is not fundamentally about leaders; rather, it is about followers first. Moreover, I contend that followers must be their own champions. Namely, we should neither lean too heavily on others, nor lose sight of the traits we presumably cherish.

To be precise, our conscience must be our greatest moral compass and our own best self our role model—so that we not only admire those who exude morality, but also exude morality ourselves. For instance, the following would be an ideal guideline: each follower must be him or herself, the embodiment of the exemplary leader that he or she would like to have. This concept is not only simple, but should be mandatory. In other words, we must take accountability for who we are, for what we do, for our decisions, for our destinies, and for our lives.

As we (followers) pursue knowledge through traditional education, along with those seven key strengths which I formerly identified, this combination will be paramount in protecting us from malicious panderers—leaders who can be characterized as wolves in sheep’s clothing—and in empowering us to become our own champions. Ultimately, this would be an effective way to sign our own writ of emancipation, and declare the exploitation of followership abolished.

Accordingly, let us seek to foster not only a new generation of principled and transformational leaders (as I suggest in the title of this Paper), but also and specially to foster a new generation of principled and transformational followers. Thus, I will delineate here the three pivotal qualities of such aspirational followers:

- They are more intellectually stern with themselves. Aspirational followers prefer to challenge their view of the world, rather than simply seeking confirmation. They accept the premise that data ultimately trumps beliefs, and firmly ground their assessments in reality. They embrace the beginner’s receptive mindset, so that when their previous perceptions differ from their current examinations of the real world, they update their understanding and welcome the new version. With this mandate in place, they are able to comprehend that it is acceptable to be wrong, and likewise that it is unforgivable to consciously remain wrong.

- They know that nothing is given, and that everything must be earned. Aspirational followers acknowledge that our current political world no longer accommodates gullible individuals, so they are unwilling to let others lopsidedly cherry-pick or nitpick information for them. They take the driver’s seat in deciding their own thoughts, and refuse to sit on the sidelines, hoping that whatever decisions the current leadership makes will be in their (followers’) best interest. They understand and practice the proactive role of followership.

- They reject being part of the problem, and long to become part of the solution. Regardless of the craziness of day to day political debate, aspirational followers do not see as an enemy everyone who has political views different from their own—rather, they see a person behind the interlocutor (not either an ally or an antagonist). They cherish pluralism and do not do “whatever it takes” to impose their opinions on others. Understanding that victory in political battles is not a goal per se, they aspire to reach the old age with the gratifying feeling that they could not have done anything better to improve society and make the world a better place—and most of the times they do that anonymously, or at least discreetly.

Followers capable of learning the seven key strengths I have described before, and of distilling the three concepts above, would serve as a perennial river, whose continuous flow and adequate filters (sharp followership acumen) would ensure a sustainable supply of pure water (outstanding quality of leadership).

This challenge must be met by this generation, then expanded by the generations to come. An encouraging place to start is from the understanding that civic actions—supposedly performed by followers—are equally important as public service—supposedly performed by leaders. Public service is, in fact, performed by leaders whom are chosen to serve the public (followers), either as elected officials by virtue of a democratic process, or as appointees ex officio by virtue of another office. This notion might also help us to make this ongoing “someone’s-turn” world become a world in which it is “everybody’s-turn” world.

An “everybody’s-turn” world can only come about through a belief in the potential of every single individual, and it will only come true if each and every one of us contribute our best efforts. This is the once in a lifetime opportunity that lies before us.

Solution, Recommendations, and Conclusion

With this worldwide vision established in the last section, I will now focus on the United States, and offer my solution, recommendations, and conclusion.

Both Democratic and Republican leaders have failed in bringing this country together—and the sidelined Independent and Third-Party figures are responsible as well. I believe that this is a fair assessment, and it becomes especially undeniable when we recollect that, throughout the campaign, the prevailing goal was to elect either an “ABC Candidate” or an “ABT Candidate” (“Anyone But Clinton” and “Anyone But Trump,” respectively), even though no one else appeared as a viable option.

One of the main causes of this state of affairs was the dysfunctional bipartisan system in the U.S., which I would describe as a one partisanship at a time system. That is, each time one of the parties is in charge, it forgets to share power with the other. At least currently, the two-party system in America strains the theoretical meaning of bipartisanship, and the lack of common ground becomes more evident every day; however, the prevalence of mutual obstructionism is not the only burden on this system.

In addition, this dysfunctional bipartisanship precludes the emergence of third options—new leaders. For example, if I say that this country was governed by only two families for two decades (from 1989 to 2009), it creates a telling picture. And I will not even elaborate on the fact that one of them almost returned to the White House last year. It is obvious that this “one partisanship at a time” system has failed to generate positive feedback loops, which could amplify the possibility of improvements in the overall ecosystem.

These distortions also have a negative impact on followers; in fact, they may even be said to originate with the followers. Wherever the origin, no one can deny the existence of a solidified domestic rivalry between the supporters of the two parties which operate within the “one partisanship at a time” system.

For example, per a Monmouth University poll, 70% of American voters affirmed that the 2016 “presidential race has brought out the worst in people.” More data could be added to substantiate this point, but as a microcosm of the big picture, the example above amply demonstrates the disproportionate belligerence we witnessed over the course of that election cycle. It is fair to infer that many Americans derive pleasure from their opponents’ losses. This sentiment is beyond concerning—both from a human perspective and from a political one. From a political standpoint, this trend preponderantly incites division, hate, and senseless rivalry.

This established and vicious cycle in American politics impacts the nation across three clear fronts: administrative, political, and personal. Perhaps Americans do not perceive this situation clearly because it is difficult to “see the forest for the trees”—especially when “the elephant” (our emotional mind) prevails over “the rider” (our rational mind).

To correct this situation, followers—that is, Americans in general—have not only to ask some difficult questions, but to answer them sincerely. As a suggestion, I formulate the following foundational question: who will be capable of leading the metamorphosis from United States of America to United People of America?

Apparently, there are no Regenerative Leaders capable of inspiring both their constituents—which is essential—and everyone else as well. I am again alluding to ability number five in our 11-attribute list defining Regenerative Leaders (“they speak not only to the hearts of their constituents, but to the hearts of the entire population, and are heard by all”).

This quality is involved in an important interplay with American Democracy. It will require Regenerative Leaders, who possess this quality, to fix the situation. Namely, these leaders must not consciously alienate segments of the population, and must conduct themselves per what is deemed best for all of Americans—individually and collectively, the “oré” and the “îandé.” I would argue that no leader should protect the “oré” at the expense of the “îandé”. These concepts are explained below.

To return to the beginnings of my own country, there was previously one form of the Tupi-Guarani language that was spoken by the Indians in Brazil, and those native Brazilians were familiar with two distinct personal pronouns for the first person of the plural. These were “oré” and “îandé.” Putting it concisely, the “oré” is the “we” that refers only to a certain part of the whole—the part in which our “friends” and ourselves are situated. By contrast, the “îandé” is the “we” that includes the entire possible universe.

That specified, let us return to the question formulated above: “who will be capable of leading the metamorphosis from United States of America to United People of America?”

Plato taught us that “the right question is usually more important than the right answer;” I am likewise aware of the complexity of this query, and would never claim to fully address it. I do hope, at the very minimum, to have formulated the “right” question here. I also hope that it will trigger further curiosity and inspire additional study and clarification on this matter. That said, for purposes of this Master’s Paper, my own straightforward response will be: current political unknowns.

From a comprehensively political standpoint, my perception is that to conduct the needed transformation, the U.S. needs leaders whom emerge from outside the ineffective “one partisanship at a time” system. If one were to put the names of all the current political leaders of this country in a cauldron and make an alphabet soup, the result would probably be indigestible. As a matter of fact, the bitterness and back-and-forth from both sides has imperiled people’s faith in current leadership.

Thus, the individuals to whom I will refer as the “Re-founding Fathers and Mothers of the United People of America,” must come from among the ranks of the current political unknowns. These could be Independents, Third-Party candidates, or yet undiscovered names in the political spectrum. Persons with this overall profile (and capable to deliver a regenerative leadership) should be put in multiple public offices across the nation.

Followers (Americans in general) can accomplish this sea change. It requires the consideration of some of the aspects formerly observed in this Master’s Paper. For instance, a thorough re-examination of “many cherished assumptions,” which must be guided by “the rider”—not by “the elephant.” In addition, attitude (first step of a long journey), motivation (persistence, resilience, struggle) and ability (capacity and expertise) should be present. And remember, to successfully break the inertia deep-rooted in the “enjoyment of our comfort zone,” the longing for change must be properly instilled in the populace in the first place.

One might argue that I have been too reductionist in my solution, that I have over generalized, or even that I lack erudition. After all, as Vleet (2010) explained: “the difference is this: the straw argument intentionally misrepresents a particular point of view in order to dismiss it, whereas reductionism often involves an over generalized explanation that precludes other explanatory factors. This may or may not be intentional, but like the straw argument, it is certainly intellectually lazy.” (p. 11)

With all due respect to those who might agree with the reasoning above, I would offer an alternative viewpoint by saying that if there is an “enemy” to be defeated here, it is a universal one (poor leadership and poor followership), and that I value the combination of critical thinking and rational behavior as a great way to approach any issue. Unfortunately, I could not apply “individualized consideration” (Nayab & McDonough, 2010) in my response and observations. I would contend that we are all within this followership-leadership framework together: this is not an individual life-or-death situation, but a collective one.

Furthermore, the “sovereign” (mutual arrangement of all citizens), should be understood as an individual person (Rousseau, 1762). Expanding upon this interpretation, just as the “sovereign” mirrors the overall will that targets the common good, my reply and observations represent an assessment that might express patterns within current American society. It is fundamental that we not cherry-pick unique demeanors, as this could be understood as a way of declaring individuals not “fully human”; according to Rousseau, entering into the “social contract” is a prerequisite for fulfilling this condition.

That said, I will now enhance the answer previously proposed. First, I would recommend to high-potential political unknowns—who are also candidates to be among the “Re-founding Fathers and Mothers of the United People of America”—to (a) develop their persuasive political acumen, and (b) have a transition plan to present to the public.

Effective political persuasion begins with the acknowledgment that we all possess different moral worldviews. Given that our political convictions are linked to our moral beliefs, it is often arduous for us to achieve any political reframing because it also demands a moral reframing. In other words, although we might know that we need to focus on what the other party values in order to persuade them to do business with us, most of the time we do not manage to look beyond what appeals to us—and this, of course, is unpersuasive. Namely, “the most effective arguments are ones in which you find a new way to connect a political position to your target audience’s moral values.” (Willer, 2015)

This notion should be tempered with a good understanding of “coalition building” (Dyke & McCammon, 2010), so that anything which inhibits effective and sustainable coalition building can be kept under control, and anything which facilitates it can be encouraged. The coalition to which I refer here might be considered a more comprehensive one, perhaps an ultimate strategic alliance. My point is that for it to be consistently successful, it must be inclusive enough both to recognize the existence of, and properly accommodate, the aspects situated beyond “shared elements.”

With this challenge in mind, “transition plans” could be developed, and their central hypothesis should be the idea of conquering maximum engagement via maximum inclusion.

Among the potential benefits of “transition plans” with such nature, I would stress the unfathomable amount of time, money, energy, and other priceless resources, which could be preserved by avoiding the all-too-frequent political showdowns which have become the pattern in recent elections—the 2016 race is ample evidence of this.

Although I cannot prove causality, I rely on the vividly clear correlation between political disputes and the current belligerence we witness in our society. In addition to suggesting that 70% of American voters felt the 2016 “presidential race has brought out the worst in people,” the Monmouth University poll previously cited also revealed that 30% of them reported that the harsh language used in politics is justified, and 7% say that they have lost or ended a friendship because of the 2016 presidential election. Based on this evidence, I trust that if campaign feuding can be ended, a more supportive and compassionate society would start to emerge.

As I offer the above overall proposition for public scrutiny, and analyze the role of followership in influencing leadership in the U.S., it might be fair to affirm that now, more than ever before, followers can foster a new generation of principled and transformational leaders. Perhaps followers can finally put into practice a precept established in ancient times: “The heaviest penalty for declining to rule is to be ruled by someone inferior to yourself. That is the fear, I believe, that makes decent people accept power.” (Plato, 380 BC)

With that all said, it is now opportune to recollect that I began this Master’s Paper by affirming that my intent was “to suggest new approaches and insights for perfecting both the follower-leader relationship—and American Democracy more broadly.” This mission statement is meant to realize a profoundly auspicious and desired tomorrow.

Therefore, I am calling for the establishment of a new type of followership (followers capable of delivering the aspirational qualities described here). I am calling for the establishment of a new type of leadership (leaders capable of delivering the regenerative attributes described here). I am calling for the establishment of a new virtuous cycle (so that we could salute the citizens of the future by saying: welcome to the dawn of a new generation of sagely transformational followers and leaders).

The crux of the matter is, inclusive followers tend to select inclusive leaders. Inclusive leaders govern in an inclusive way and also foster inclusivity in new leaders. These new leaders inspire—and are inspired by—their inclusive followers, whom, in turn, continue to elect inclusive leaders. In conclusion, this is the virtuous cycle we must relentlessly pursue.

References

Hersey, Paul, & Blanchard, Kenneth H. (1985). “Situational Leadership”

Diogo, Eduardo (2017). “It Was About Hope: Fact-Based Analytic Research. Untold Stories. And More…”

Bass, Bernard M. (1985). “Bass Transformational Leadership Theory”

“Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study”

“Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA)”

“CNN/ORC Poll,” conducted among September 4-8, 2015

Stake, Robert (2005). “Multiple Case Study Analysis”

Klenke, Karin (2008). “Qualitative Research in the Study of Leadership.”

Kristof, Nicholas (2016). “Is Hillary Clinton Dishonest?” (The New York Times)

Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). “Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development.”

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). “Meta-Analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues.”

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). “Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective.”

Howell, J. M., & Hall-Merenda, K. E. (1999). “The ties that bind: The impact of leader-member exchange, transformational and transactional leadership, and distance on predicting follower performance.”

Ahler, Douglas J. (2014). “Self-Fulfilling Misperceptions of Public Polarization.”

Prentice, Deborah A., & Miller, Dale T. (1996). “Pluralistic Ignorance and the Perpetuation of Social Norms by Unwitting Actors.”

Haidt, Jonathan (2015). “Tale of Behavior Change”

Lewin, Kurt (1940). “Change Model: Unfreeze, Change, Refreeze”

Yalom, Irvin D. (1995). “The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy”

Sherman, Stratford, & Freas, Alyssa (2004). “The Wild West of Executive Coaching” (Harvard Business Review)

Monmouth University Polling Institute (September 28, 2016). “National: 2016 Brought Out Worst in People.”

Vleet, Van Jacob E. (2010). “Informal Logical Fallacies: A Brief Guide”

Nayab, N. & McDonough, Michele (2010). “Characteristics of Transformational Leadership”

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1762). “The Social Contract,” originally published as “On the Social Contract;” or, “Principles of Political Rights.”

Willer, Robb (2015). “New research shows how to make effective political arguments.” (Stanford News)

Dyke, Nella Van, & McCammon, Holly J. (2010). “Strategic Alliances: Coalition Building and Social Movements”

Plato (380 BC). “The Republic”